I’ve always known that my existence will always be political. I don’t think I understood it in those exact words growing up, and I don’t think I understand it in the more concrete ways in which I do now. I just know that there is a specific mold that society prefers people to be, and I don’t fit in to that mold. As the years go by, that becomes clearer.

What mold am I talking about? Well, one that’s forced by patriarchal, heteronormative, white supremacist, ableist ideas. As a brown woman, I for sure don’t fit into that mold. When structural systems of power depend entirely on this mold, existing as yourself outside of that mold is in and of itself a struggle for power. It’s political.

Many people who know me also know that I was born in Texas, but grew up in Bogor and Jakarta, Indonesia. I moved to Washington state when I was 15. First to Vashon, then Auburn, then Seattle. That wasn’t a very typical coming-of-age experience, for an American nor an Indonesian.

As a kid I was really active. I still am as a dancer, but when I was younger I loved playing sports. I did Karate and Tae Kwon Do, was on the basketball team and later the soccer team, and had a brief stint with the swim team. Being outside in a tropical region means the sun shines really bright and for the most part I was always tan (I was already dark-skinned to begin with). When I was younger, before I was even 10, I think, my aunts would say to me: “It’s okay that you’re dark-skinned now, your skin will get lighter when you grow up and you’ll be pretty.”

Growing up, I didn’t really have dolls that looked like me. I had Barbie dolls, and Barbie dolls weren’t brown and small and queer back then. They’re still not.

When I was in elementary school, I had a few guy friends, and each one of us had nicknames. Mine was “ant,” because to quote them, I was “small, black, and stupid.” They were joking about the stupid part, because they knew I was smarter than all of them, but I was still the small, black girl. (It’s funny looking back at this now because now, Black to me is a very distinct identity that I very much don’t posses, but in Indonesia if you weren’t light skinned then you were considered “black”)

Throughout most of my primary school years, I understood that I would not be called “pretty.” For some reason, the Indonesian words for “pretty” or “beautiful” were often reserved for people who are light-skinned. If you were dark-skinned, the go-to words were “exotic” or an Indonesian phrase that directly translates to “black and sweet” (”hitam manis”).

When I moved to the US, a lot of people in Vashon didn’t know where Indonesia was. One girl asked me: “Is that like near India?” Or they would ask the all-time favorite: “I know Bali, do you know Bali?” because that’s the only thing they’ve heard of Indonesia, and they heard about it from Eat, Pray, Love. Yawn. Yes, white girl, of course I know where Bali is. Good for you for being so cultured.

During this past Thanksgiving weekend, my Indonesian friends and I went to Poulsbo. On the ferry to Bainbridge Island, we sat at a booth on one side of the ferry. Everyone on every other booth on our side in the cabin was white. This white lady was going booth to booth to register voters. She took a look at our booth and skipped it. We were all brown. I am an American citizen who has voted in every election since I turned 18. The lady didn’t even bother to ask.

Once, after a discussion in my dance history class on cultural appropriation within dance, a white girl friend of mine asked “Why can’t dance just be dance?” She proceeded to look at me and said “I know why you think it can’t, but I feel like dance should just be dance,” as though it’s my fault and my problem that I can’t get over the politics within things (even dance! gasp!)

One time I was reporting on an event on climate justice, and I was shadowing some canvassers who went around Columbia City to get the perspectives of marginalized, low-income, racial minorities on how climate change issues impacted them. I was shadowing canvassers who were interviewing a Black, homeless veteran. He didn’t answer the questions they asked right away but instead proceeded to wonder out loud about my ethnicity. He said “You can’t be Indian because you’re not dark enough, but you can’t be Vietnamese because your skin is not light enough, but the Vietnamese women are the most beautiful, so what are you?” Upon knowing that I’m Indonesian, he said “Ah, a Polynesian princess. Your ancestors must be beautiful.” I went home after and cried.

Every time I go back to Jakarta now, it’s always hard to switch languages at first, and from time to time the tiniest hint of an American accent would slip. My friends would call me a term that translates to “foreigner,” but it’s only used when referring to white foreigners. I was never a fan of that. When I go back to Seattle, I’m still the foreigner because I’m brown and Indonesian and have an “exotic” name.

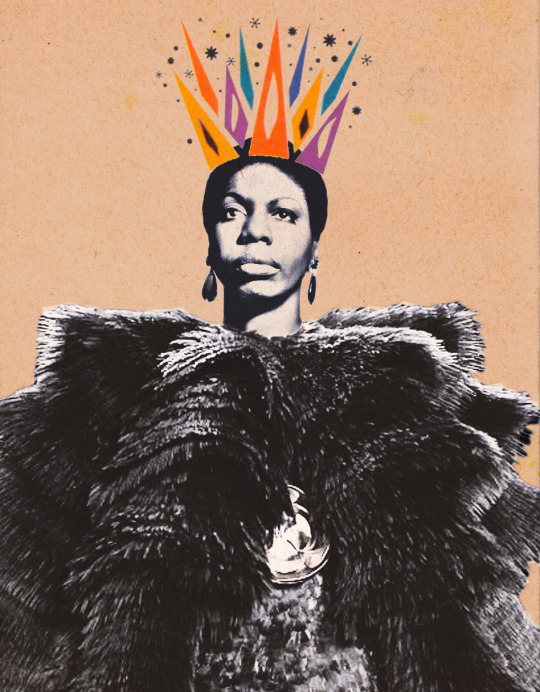

Why am I writing about all these stories? Well, I recently made a dance piece that wasn’t explicitly about these stories but is very much influenced by these experiences (and more) and how they affected my worldview. It’s going to be premiered next week. It’s scary as fuck. Not because I don’t think people are going to like it or that it’s not going to be good (because I don’t really care about the first one and I am confident that it’s a good piece), but because I know there will be people watching who will put me in a box.

Seattle is a very white city. I’m not a white person. I’m reflecting on my experiences as a person of color who juggles these identities and these ideas of home as an American and an Indonesian. I’m using non-Western music, the title’s going to be in Old Javanese language, and I’m brown.

The thing is, I’ve never done this before. I’ve never explicitly put these ideas about my identity on stage before, despite always juggling these ideas in my brain, writings, and everyday conversations. It usually just filters through in my stage works. Everything I’ve made as a choreographer up to this point has always been a work of research: I explore universal concepts, I investigate the experiences of others, I analyze discourse on certain things. I still do all of that with this work because that’s always been my process, but there’s a very personal and very sentimental element at play here, because in a way, I’m blurting all the things I’ve written about above—and more—in the piece, but not explicitly and the viewers won’t really know it (and that’s okay). It’s time I put these ideas on stage.

The thing is, because Seattle’s a white city and the tastemakers in the dance scene are mostly white and grew up influenced by a North-American perspective on what home means and what growing up was like, they won’t get how hearing the sound of traditional Indonesian gamelan makes me feel like I’m in 4th grade, learning how to play the instruments. How that reminds me of childhood and innocence. They won’t get how the highs and lows of sindhen vocalists make me feel like I’m being sung a prayer that keeps bad things at bay. How that makes me feel safe. A lot of people will think it’s just “ethnic” music. People may think, “Of course she would make something like this she’s Indonesian,” and proceed to think that I’ll be the go-to for Indonesian knowledge and only that. People may not know about how frustrating it is to feel foreign in the places you call home, how guilty you feel when you find yourself complicit in white hegemony as a person of color. Some people may think that I’m just trying to be edgy in trying to “blend Eastern and Western cultures.”

The thing is, white-cis-straight people make stuff based on their past life experiences all the time, and they don’t have to worry about having that experience fetishized the crap out of itself. Because their experiences are considered the default, therefore relatable. Mine’s foreign. It’s exotic.

The thing is, I don’t really know why I’m writing all this. I’m writing this at 2 a.m. after an 8-hour stint of covering the news at work. I’m anxious and nervous and excited and drinking so much wine, just like any choreographer would be a week before a premiere. I’m not writing this to be preachy or offer a solution. I’m writing this because some people in white Seattle are going to watch my piece and exoticize the hell out of it and I’m the one worrying about it, as opposed to them realizing that that’s not okay. And that frustrates me.

The thing is, I don’t need people to think a certain thing when they’re viewing my work, I’ve never thought that ever. That’s the beauty of art right? Viewers get to layer their own experiences on it. But it sucks knowing that some people are going to put you in a box because they just grew up differently than you. And somehow you’re the one that gets stripped of your complexity, because the white hegemonic system makes it real convenient to do so.

Any artist presenting work has a million different things in mind, and there are a lot of inherent risks within that existence. For many artists, those risks are why they became artists in the first place. But if you’re an artist of color, and you’re putting your experiences into a work and acknowledging your brownness or blackness, there’s a seemingly inherent risk: That people are going to watch and some of them will think “Of course they would make this, this is what they know,” as though it’s your fault for not “getting over” your existence as a person of color and not instead joining the white artists that are out there “objectively” researching elusive ideas. That’s real frustrating, and that’s not a sustainable art-making environment.

But I don’t know, I guess at the end of the day, we as people of color are going to just deal with shitty systems, whether in art or politics or economics or whatever. And we’re gonna stick with each other and support the hell out of each other in the process. In the words of the late, great Mark Aguhar:

“It’s that thing where the only way to cope with the reality of your situation is to pretend it doesn’t exist; because flippancy is a privilege you don’t own but you’re going to pretend you do anyway.“

And yet despite how dreary it may feel, it’s also kind of empowering in a way. These words from musician Meredith Graves really speak to me:

“For most of us, [combining art and activism is] unavoidable. As long as art, like music, remains predominantly a cis-straight-male scene, any art made by a person who doesn’t fit those parameters is a form of activism. It’s not that you have to be overtly political or run around on stage screaming like I do—you can make quiet, dreamy music or weave or do silent performance art or just insist on existing in volatile spaces, and it’s still an insanely radical act. Giving yourself permission to exist is both activism and a form of art.”

I guess now that I think about it, I’m writing this for the black and brown folks out there making art and I just want to say: you’re not alone, and you got this.

-i